A Tale of Two Women

“I always felt like a victim as well as Emmett. He came in our store and put his hands on me with no provocation. Do I think he should have been killed for doing that? Absolutely, unequivocally, no! Did we both pay a price for it, yes, we did. He paid dearly with the loss his life. I paid dearly with an altered life.” Carolyn Bryant

On August 29, 1955, an arrest warrant for the kidnapping of Emmett Till was issued for Carolyn Bryant of Money, Mississippi. The warrant was never executed, and the document was buried in boxes of documents, unknown to authorities. Surprisingly, the warrant was recently uncovered, and on August 9, 2022, almost 67 years later, a grand jury declined to indict her. A similar decision not to indict for manslaughter was made in 2007. Carolyn Bryant is 88 years old.

“With each day, I give thanks for the blessings of life—the blessings of another day and the chance to do something with it. Something good. Something significant. Something helpful. No matter how small it might seem. I want to keep making a difference.” Mamie Till Mobley

Mamie Till was born Mamie Elizabeth Carthan in Webb, Mississippi. During the Great Migration of southern blacks to the north, her family moved to the Chicago area when Mamie was a small girl. After her parents divorced, Mamie focused on her school studies, making the A honor roll, and graduating high school. At age 18, she met Louis Till. Despite her parents’ disapproval, Mamie married Louis in 1940. Nine months later, Emmett Till was born.

The marriage was not a happy one, with Louis Till unfaithful and physically abusive to Mamie. After repeatedly ignoring restraining orders imposed by a judge, Louis Till was given a choice of jail or the military. Louis joined the army in 1943. In 1945, Mamie was notified by the army that Louis had died of “willful misconduct.” In truth, he had been subsequently accused of two counts of rape and one count of murder in Italy and hung by order of a military court-martial. The entire circumstances of his death did not fully emerge until ten years later.

In 1951, Mamie married Pink Bradley, a union that only lasted a year. For the next three years, Mamie was left to work and raise her son Emmett as a single mother. Mamie still maintained family relationships in Mississippi, having frequently visited her Uncle Moses Wright and her nephews. In 1955, Emmett was 14 years old and had planned a visit to Mississippi alone and spend time with his great Uncle and cousins. He left Chicago on August 20th, bound for Money, Mississippi.

Carolyn Bryant was born in 1934 in Indianola, Mississippi. Her father was a plantation manager, her mother a nurse. Carolyn dropped out of high school to marry Roy Bryant, a local grocery store owner—Bryant’s Grocery & Meat Market—with a clientele of black sharecroppers and their children. The store was located in the tiny town of Money, Mississippi, the hub of the cotton-growing Mississippi Delta. They had two sons and lived in two small rooms in the back of the store. Carolyn later divorced her husband Roy and married two more times.

On August 24, 1955, Roy Bryant was in Texas on a truck owned by his brother, delivering shrimp. His wife, Carolyn, was left in charge of the grocery store, kept company and assisted by her sister-in-law, Juanita Milam. Juanita was married to Roy’s half-brother, J.W. Milam.

As told by journalist William Bradford Huie:

“About 7:30 pm, eight young Negroes -- seven boys and a girl -- in a '46 Ford had stopped outside. They included sons, grandsons, and a nephew of Moses (Preacher) Wright, 64, a 'cropper. They were between 13 and 19 years old. Four were natives of the Delta and others, including the nephew, Emmett (Bobo) Till, were visiting from the Chicago area.”

On August 24, 1955, the worlds of Carolyn Bryant—the product of a segregated Jim Crow South—and Mamie Till—raised in the more enlightened urban north—collided.

Emmett arrived in Mississippi on August 21st. Four days of family and fun finally turned to tragedy. The horrific details of what happened on August 25th, August 28th, and the subsequent months are well known (timeline from American Experience)

August 24, 1955

Emmett joins a group of teenagers, seven boys and one girl, to go to Bryant's Grocery and Meat Market for refreshments to cool off after a long day of picking cotton in the hot sun. Bryant's Grocery, owned by a white couple, Roy and Carolyn Bryant, sells supplies and candy to a primarily black clientele of sharecroppers and their children. Emmett goes into the store to buy bubble gum. Some of the kids outside the store will later say they heard Emmett whistle at Carolyn Bryant.

August 28, 1955

About 2:30 a.m., Roy Bryant, Carolyn's husband, and his half-brother J. W. Milam, kidnap Emmett Till from Moses Wright's home. They will later describe brutally beating him, taking him to the edge of the Tallahatchie River, shooting him in the head, fastening a large metal fan used for ginning cotton to his neck with barbed wire, and pushing the body into the river.

August 29, 1955

J. W. Milam and Roy Bryant are arrested on kidnapping charges in LeFlore County in connection with Till's disappearance. They are jailed in Greenwood, Mississippi and held without bond.

August 31, 1955

Three days later, Emmett Till's decomposed corpse is pulled from Mississippi's Tallahatchie River. Moses Wright identifies the body from a ring with the initials L.T.

September 1, 1955

Mississippi Governor Hugh White orders local officials to "fully prosecute" Milam and Bryant in the Till case.

September 2, 1955

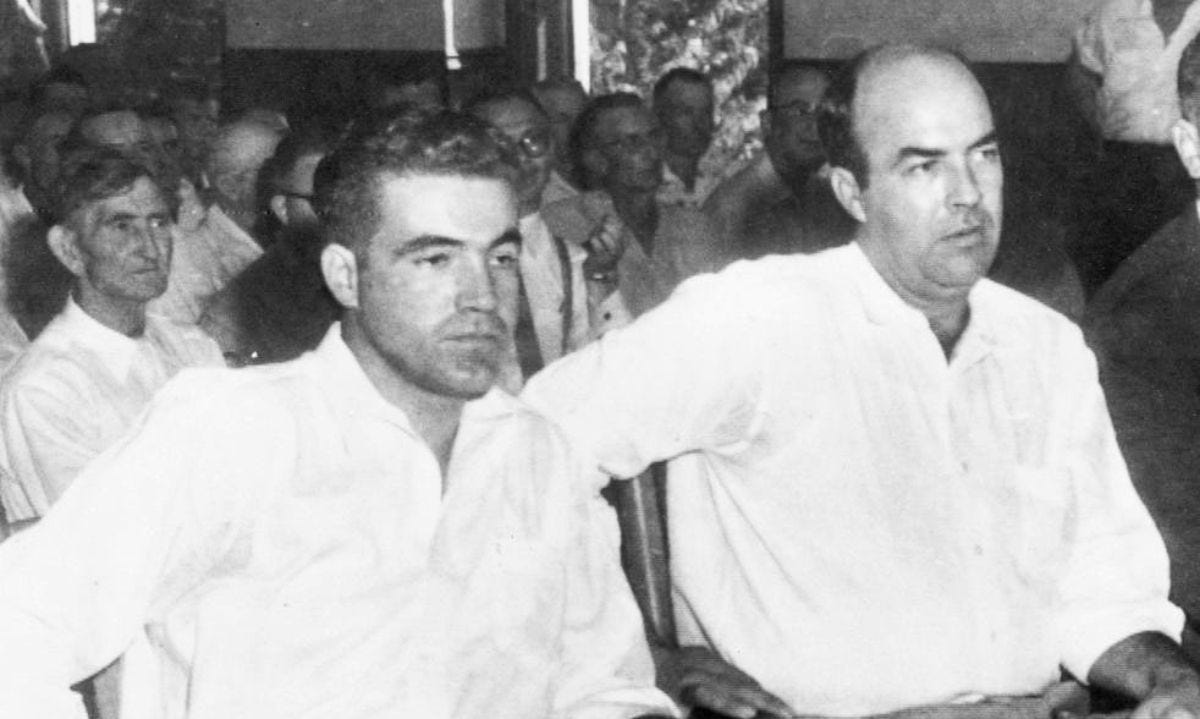

In Chicago, Mamie Till arrives at the Illinois Central Terminal to receive Emmett's casket. She is surrounded by family and photographers who snap her photo collapsing in grief at the sight of the casket. The body is taken to the A. A. Rayner & Sons Funeral Home.

September 3, 1955

Emmett Till's body is taken to Chicago's Roberts Temple Church of God for viewing and funeral services. Emmett's mother decides to have an open casket funeral. Thousands of Chicagoans wait in line to see Emmett's brutally beaten body.

September 6, 1955

Emmett Till is buried at Burr Oak Cemetery.

In Mississippi, a grand jury indicts Milam and Bryant for the kidnapping and murder of Emmett Till. They both plead innocent. They will be held in jail until the start of the trial.

September 15, 1955

Jet magazine, the nationwide black magazine owned by Chicago-based Johnson Publications, publishes photographs of Till's mutilated corpse, shocking and outraging African Americans from coast to coast.

September 19, 1955

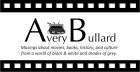

The kidnapping and murder trial of J. W. Milam and Roy Bryant opens in Sumner, Mississippi, the county seat of Tallahatchie County. Jury selection begins and, with blacks and white women banned from serving, an all-white, 12-man jury made up of nine farmers, two carpenters and one insurance agent is selected. Mamie Till Bradley departs from Chicago's Midway Airport to attend the trial.

September 20, 1955

Judge Curtis Swango recesses the court to allow more witnesses to be found. It is the first time in Mississippi history that local law enforcement, local NAACP leaders and black and white reporters team up to locate sharecroppers who saw Milam's truck and overheard Emmett being beaten.

September 21, 1955

Moses Wright, Emmett Till's great uncle, does the unthinkable -- he accuses two white men in open court. While on the witness stand, he stands up and points his finger at Milam and Bryant and accuses them of coming to his house and kidnapping Emmett.

September 23, 1955

Milam and Bryant are acquitted of murdering Emmett Till after the jury deliberates only 67 minutes. One juror tells a reporter that they wouldn't have taken so long if they hadn't stopped to drink pop. Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam stand before photographers, light up cigars and kiss their wives in celebration of the not guilty verdict.

September 30, 1955

Milam and Bryant are released on bond. Kidnapping charges are pending.

November 9, 1955

Returning to Mississippi one last time, Moses Wright and Willie Reed testify before a LeFlore County grand jury in Greenwood, Mississippi. The grand jury refuses to indict Milam or Bryant for kidnapping. The two white men go free.

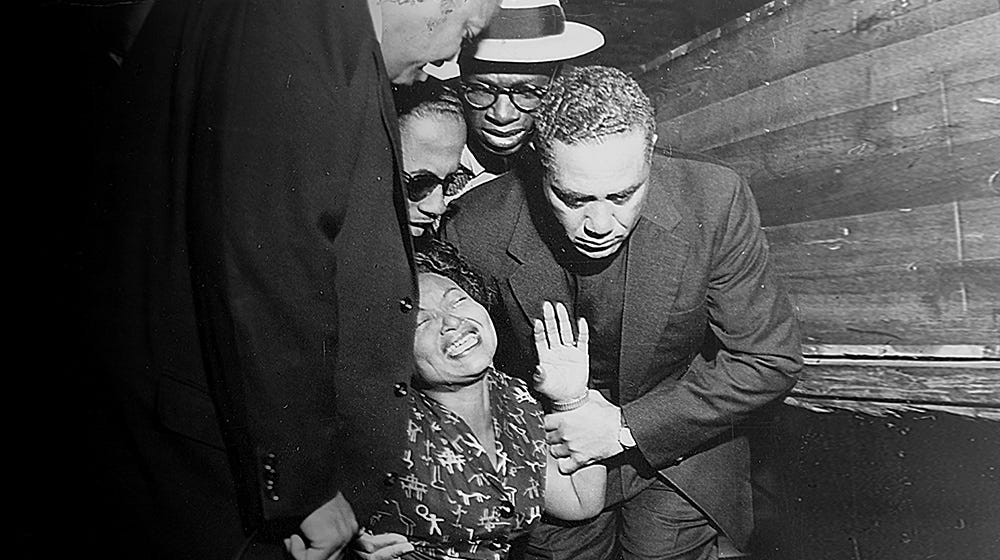

For the following decades, Mamie Till and Carolyn Bryant reacted to the adversity in diametrically opposed ways. Mamie made the courageous decision to provide an open casket, exposing and sharing the atrocity of Emmett’s lynching with America. Jet magazine told her story and shared photos of Emmett Till, sharing her grief with the entire world. Her story inspired Rosa Parks to keep her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama school bus, sparking the wider civil right moment.

Years later, Jesse Jackson asked her why she refused to move to the back of bus. She [Rosa Parks] replied, “I thought of Emmett Till and I couldn’t go back.”

Vanessa Pius, writing for the National Parks Conservation Association, sums up Mamie’s post Emmett life—teacher, speaker, civil rights advocate:

Mamie served as a powerful speaker and teacher for the rest of her life.

After the trial, demonstrations broke out across the country and around the world. Mamie was flooded with speaking requests, and after each one, the NAACP experienced a huge influx of donations and new memberships. The month after the trial, Mamie was sometimes making two or three speeches a day, and though she was still struggling with her own grief, she felt a strong sense of importance around sharing Emmett’s story.

Eighteen years after Emmett’s death, while serving as an elementary school teacher, Mamie founded the Emmett Till Players, a touring troupe of young students who delivered speeches about hope, unity and determination. Inspired in part by Martin Luther King Jr.’s speeches, Mamie saw how public speaking could teach students history, confidence and discipline. She wanted students to understand the immense sacrifices that others had made for the opportunities and freedom they had, so naturally, she named the program for Emmett.

Mamie continued speaking throughout the country until her death in 2003, connecting with mothers of other slain Black children and making sure no one ever forgot her son’s story.

She closes her autobiography by writing, “Although I have lived so much of my life without Emmett, I have lived my entire life because of him.”

Mamie Till-Mobley dedicated her life to seeking justice for her son Emmett and to supporting and educating young people.

Conversely, Carolyn Bryant slithered into hiding, maintaining her false accusations in an unpublished memoir I Am More Than a Wolf Whistle:

The door opened and a young black man, who appeared to me to be in his late teens or early twenties, entered the store. I found out later that this young man's name was Emmett Till… Once there, I asked him if Icould help him. He asked me for some candy, gum or some type of sweets. We had jars of candy and cookies on the top of the counter. I opened the case door to get the items he pointed out the items he wanted to buy. Imentally totaled the amount he owed. He reached for the small bag of candy from the top of the counter. When I held out my hand for the money, he put no money into my hand, but instead, he caught my hand and told me in a clear voice, "Don't be afraid of me,I've been with white girls before." Whether he stuttered or stammered, I don't recall. I was afraid. His grip was strong as he held my hand from across the counter. Complete astonishment, then fear filled my mind. He asked me, "How about a date, baby?" My mind raced. I feared thought he was going to molest me or worse. I was afraid for myself, and my babies. My babies were in the back room. He then grinned at me as I jerked my hand free from his and dashed towards the main counter to get Roy's pistol. When I reached the open space between the counters, the young man Emmett was there. He had slipped through and caught me with both of his hands on my hips. He was saying to me, "What's the matter, baby, can't you take it?" I became even more frightened, as he was much larger and taller than I. "Oh my God, what is going to happen? What is he going to do to me?" were the thoughts that raced through my mind. I continued to struggle to get free from his grasp. As I was struggling, he said, "You needn't be afraid of me, I've f-ked white women before." I was about to explode with fear as the seconds flew by. Never before, nor since, have I been that afraid. I screamed for help, but no one responded. I was afraid and alone. I was shaking all over, because nothing like this had ever happened before. I'd always felt safe in the store, but now, I was afraid. I jerked and twisted as hard as I could and I could feel the strong grip loosen from around my hips. Once free, I saw another young man pulling Emmett away from me. The young man was telling Emmett, "Come on, come on, we got to get out of here."

Simeon Wright, Emmett’s cousin who was present, confirming Emmett did wolf whistle at Bryant, but disputes the accusations of physicality in his book Simeon’s Story. Jerry Mitchell, legendary civil rights journalist, and Devery Anderson, a Till scholar, dispute Bryant’s claims as well and characterize Bryant as a liar and self serving participant.

In 1956, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam, protected by immunity from prosecution, gave an interview to William Bradford Huie, a journalist. Huie paid $4000 for the exclusive, and created a vehicle for Emmett Till false narratives.

Carolyn Bryant continued in that same vain with the sharing of her unpublished memoir. In the waning years of her life, Bryant has come out of hiding to perpetuate distortions and self pity, equating her hardships with the death of a 14 year old boy and the lifetime of grieving for his mother—Mamie Till.

In 1957, Mamie finally found personal happiness with her third husband, Gene Mobley. But it’s her public contributions that created inner peace. Let’s remember and celebrate Mamie Till dedicating her life to helping others, selfless, sharing her hell with the world so society could better itself; juxtapose that with Carolyn Bryant hiding in obscurity, a bitter old woman, relegated to her tragic part in history.

Two women could not have taken diametrically opposed paths in life. Mamie Till has earned our respect and admiration, as she will be honored and remembered (she died January 6, 2003) for her work and legacy, her grace, courage, and contributions.

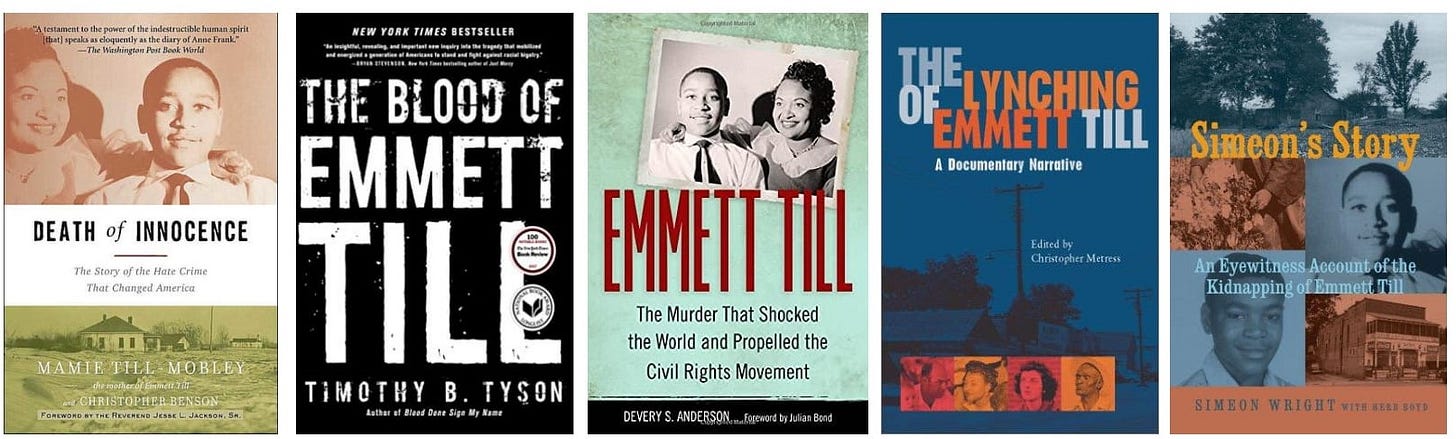

FURTHER READING

AS ALWAYS, THANK YOU!